Exploring Environmental Justice & Energy Equity in North Carolina: Introduction to Environmental Justice and Federal Programs

By: Dawn Haworth, Communications Intern

This is the first post of a three part blog series that examines the progress being made to advance Environmental Justice from a clean energy standpoint. The series will cover federal programs and incentives that aim to benefit historically disadvantaged communities, and how those initiatives impact communities at the state and local level.

What is Environmental Justice and when did it become well-known?

Throughout history, environmental, health, and economic impacts have disproportionately affected communities of color across the United States. In 1982, residents of Warren County, North Carolina sparked national public awareness about an injustice their community was facing. The state had proposed construction of a new landfill in the town of Afton, within Warren County, which was intended to hold truckloads of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) contaminated soil. After three lawsuits and several public hearings, the state’s plan was approved. The residents conducted a nonviolent protest against the landfill by marching and blocking the road to prevent trucks carrying waste to reach the dumping site. The non-violent protests continued for six weeks resulting in over 500 people being arrested. In the end, the residents lost their battle, and the state succeeded in dumping the waste in Warren County.

Although the state had eventually pushed forward with their plans, the resilience and strength of Warren County residents struck a chord in communities across the nation. After carrying the burden of environmental impacts for decades, they finally had representation and national attention. Studies began to analyze these disproportionate impacts, one being conducted by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 1983, that reported in eight southeastern states, three quarters of hazardous landfill sites were located in low-income communities of color.

During this time, the term Environmental Justice (EJ) was coined by scholars and activists Robert Bullard, Paul Mohai, Robin Saha, and Beverly Wright. Finally, communities began to see progress in the United States, however, the first Executive Order (EO) regarding EJ was not issued until 10 years after the Warren County protests. EO 12898 was issued in 1994, and directed agencies to come up with a strategy for implementing EJ and to address its effects.

What role does policy play in Environmental Justice?

Public funding at the federal and state levels is essential to providing communities with greater access to necessary resources. Government programs can cover a wide range of services that will support initiatives to benefit those who may be underserved. Federal investments and grants are often intended to trickle down in order to support workings at the state level.

This blogpost will cover the initiatives and programs that have recently become available at the federal level, and subsequent blogs will explore what North Carolina is doing in terms of EJ.

What initiatives have been taken at the federal level?

Justice 40

The next major EJ related Executive Order comes three decades after EO 12898, and is referred to as “Justice40”. The Justice40 Initiative was introduced in 2021, when President Biden made a commitment in Executive Order 14008 to allocate 40% of Federal investment benefits to disadvantaged communities that have been historically underrepresented, underserved, and burdened by environmental issues.

There are seven categories of investments that apply to the initiative:

- Climate change

- Clean energy & energy efficiency

- Clean transit

- Affordable & sustainable housing

- Training & workforce development

- Remediation and reduction of legacy pollution

- Development of critical clean water and wastewater infrastructure

Following the Executive Order, the White House provided Interim Implementation Guidance to Federal agencies in July 2021, directing them to identify which programs are covered under the Justice40 Initiative and to start implementing reforms to those programs. Programs covered under the initiative are those that include investments that will benefit disadvantaged communities in one or more of the seven categories. A covered Justice40 investment includes any grant or procurement spending, financing, staffing costs, or direct spending or benefits to those in a Justice40 covered program.

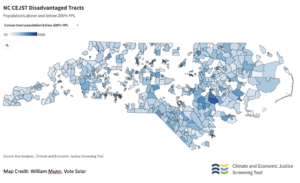

In January 2023, agencies were given additional guidance on how to use the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool, or CEJST.

What is CEJST?

CEJST is a mapping tool that aids in identifying disadvantaged communities. In the 2023 guidance, disadvantaged communities (for the purpose of CEJST) are defined as “either a group of individuals living in geographic proximity to one another, or a geographically dispersed set of individuals (such as migrant workers or Native Americans), where either type of group experiences common conditions.” Federally Recognized Tribes are also designated as disadvantaged communities. This guidance also allows agencies to refer to disadvantaged communities as “Justice40 communities” in their materials.

Census tracts are determined as disadvantaged in CEJST if they meet the threshold for environmental and associated socio-economic burdens. The eight categories of burden as defined by CEJST are:

- Climate change

- Energy

- Health

- Housing

- Legacy pollution

- Transportation

- Water and wastewater

- Workforce development

Additionally, if a census tract is completely surrounded by disadvantaged communities and is equal to or greater than the 50th percentile for low income, the tract is also considered disadvantaged.

Federal agencies were expected to have implemented CEJST for new Justice40 investments or covered programs by the start of fiscal year 2024. The aim is for this mapping tool to become the primary method used by agencies to identify disadvantaged communities geographically. There are circumstances that allow exceptions to this expectation, in the case that an agency is using another tool to identify these communities, or if there is a need to identify other areas considered as disadvantaged using another method. CEJST is anticipated to be updated annually, and new instructions will be issued by the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) in the future to highlight any changes that are made.

Inflation Reduction Act

Another important piece of legislation signed by President Biden is the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which introduced an array of programs aimed to assist low-income communities and individuals. The Biden Administration describes the IRA as “the largest investment in clean energy and climate action ever.” Since being signed into law in 2022, the act has introduced many incentives and programs to support a clean energy economy in all communities. As a whole, the IRA provides around $400 billion to create and improve programs.

Home Energy Rebates

Of the $400 billion, $8.8 billion was allocated towards the Home Energy Rebates program. This program encompasses two parts: Home Efficiency Rebates (HER) and Home Electrification Appliance Rebates (HEAR). Although this was introduced in 2022, the rebates are not yet available. The Department of Energy (DOE) anticipates that states will begin their programs in 2024, which can be tracked by this map.

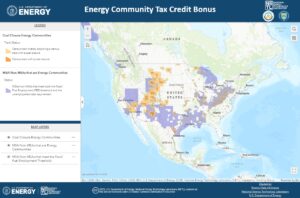

Energy Community Tax Credit Bonus

The IRA defined an Energy Community Tax Credit Bonus that is designed to give back to communities whose economies have been or could be negatively impacted by the presence of coal and power plant industries. The DOE has developed a mapping tool that can be used to locate which areas fall under the requirements for the tax credit.

Low Income Communities Bonus Credit Program

The Low Income Communities Bonus Credit Program is another incentive introduced by the IRA. This credit is used to support qualified solar and wind energy facilities to prioritize the access of renewable energy in underserved communities. The DOE has developed a mapping tool for this credit as well to locate geographic eligibility to apply. For more information about this program, visit this page created by the Office of Energy Justice and Equity.

Direct Pay Provision

The IRA included a provision referred to as “elective pay”, or “direct pay” that will allow governments and tax-exempt organizations to receive the full value of tax credits for implementing clean energy projects. This is designed to make clean energy projects more accessible in local communities by decreasing costs. Those currently eligible for direct pay are State, Local, and Territorial Governments, Tribal and Native Entities, Rural Energy Cooperatives, and other tax-exempt entities. This page published by the White House has more information on direct pay and those who are eligible.

Environmental and Climate Justice Program (ECJ)

Another program under the IRA is the Environmental and Climate Justice Program (ECJ) which provides funding and technical assistance for climate justice projects that will benefit underserved communities. This program is led by the EPA, and has been given $2.8 billion for funding and $200 million for technical assistance that needs to be awarded by September 30, 2026. The EPA has distributed this funding among several new initiatives: Community Change Grants, EJ Thriving Communities Grantmaking, EJ Collaborative Problem-Solving Cooperative Agreement, EJ Government-to-Government, and Engagement Opportunities. More information about this program and its many subsets can be found here.

Programs from the IRA are key contributions to advancing Environmental Justice at the federal and state levels. Just Solutions Collective estimates that $40 billion will go directly to benefitting underserved communities. This table from Harvard gives a visualization of the many EJ provisions of the IRA.

It is necessary that programs and incentives intended to benefit marginalized communities are made accessible to individuals within those communities. The next blogpost will dive into how these federal programs and incentives are applied at the state level, and look into the workings of the NC Department of Environmental Quality as it relates to energy equity.